In the Shea Belt: How Ghana and Burkina Faso Became the Heart of a Global Ingredient

Inside the untold story of Shea butter — from sacred trees and women-led cooperatives to global cosmetic aisles and the quest for fair value.

Step into any high-end cosmetic store, pick up a moisturiser, lip balm, or hair mask, and chances are you'll spot a common ingredient: Shea butter.

Creamy, rich, and naturally derived, Shea butter has quietly become a multi-billion-dollar commodity powering the skincare industry.

But behind the clean packaging and “organic” labels lies a complex, deeply human story that begins in the heart of West Africa — in the Shea Belt — where the trees grow wild and the butter is still, in many places, made by hand.

At the center of this story are Ghana and Burkina Faso — two neighbouring countries with shared geography, intertwined trade routes, and a long-standing cultural and economic relationship with the Shea tree.

What connects them isn't just trade or proximity.

It’s tradition, resilience, and a unique ecosystem where a single wild crop sustains millions of lives.

This is the story of Shea butter, and how two countries — often underappreciated in global supply chains — became critical players in a rapidly growing industry.

A Tree That Grows Without Asking

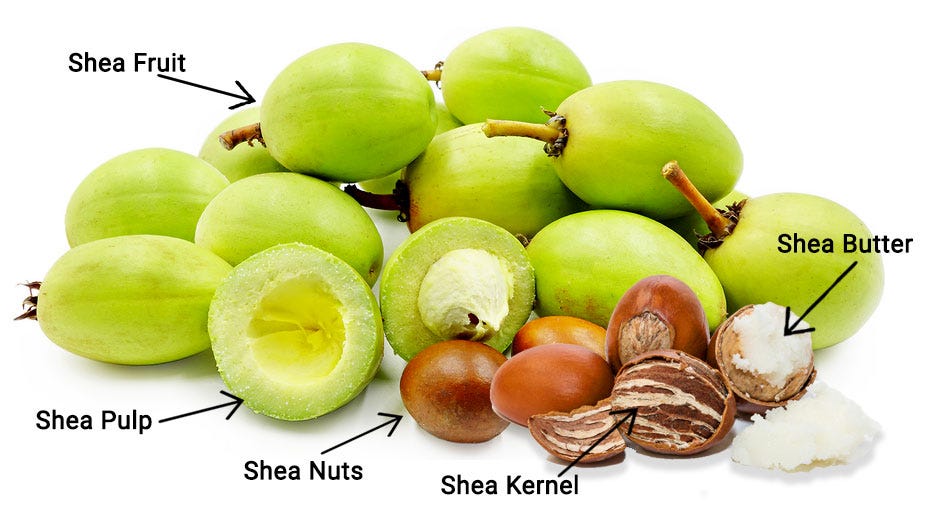

The Shea tree, known scientifically as Vitellaria paradoxa, is unlike most commercial crops. It doesn’t grow in neat rows or under managed conditions. It grows wild — primarily in dry savannah zones — and can take up to 15 years to mature and start fruiting.

There’s no commercial plantation model for Shea yet. Instead, it thrives in nature, deeply integrated into the lives and traditions of rural communities.

The area in which the Shea tree grows naturally is often referred to as the Shea Belt, stretching across 21 African countries from Senegal in the west to Uganda in the east.

But the highest quality Shea nuts, and the most developed Shea-related economies, are found in West Africa — particularly Ghana and Burkina Faso.

This region is home to millions of Shea trees, many of them protected by customary land rights and passed down through generations.

In some communities, cutting down a Shea tree is forbidden — not because of laws, but out of respect for what the tree represents.

Shea Butter: More Than a Product

Shea butter is a fat extracted from the nuts of the Shea tree. Its properties are remarkable: high in vitamins A and E, with natural anti-inflammatory and healing qualities.

In the West, it's a luxury ingredient. In West Africa, it's a daily essential.

Traditionally, women use Shea butter for cooking, as a base for medicinal ointments, and as a skin and hair moisturiser in the dry Sahel climate.

It's applied to newborns, used in wedding preparations, and even plays a role in funerary rituals.

In other words, Shea isn’t just an export item — it's embedded in the social fabric.

A Cultural Legacy Centuries in the Making

The historical use of Shea butter in West Africa goes back centuries, perhaps even millennia. Ancient caravans travelling across the Sahel are believed to have carried Shea butter in clay pots as part of their trade.

In medieval Mali and Songhai empires, Shea butter was prized not only for personal care but for treating wounds, softening leather, and protecting skin from the harsh desert sun.

In many West African oral histories, the Shea tree is referred to as a "gift from the gods". Among the Dagomba and Mamprusi communities of northern Ghana and southern Burkina Faso, Shea trees are seen as sacred.

Some traditions prohibit felling them, and in others, the trees are planted to mark significant family events like childbirth or inheritance.

Shea butter has also played a role in community healing, particularly in preparing herbal concoctions or serving as a carrier for traditional medicine.

In many cases, it was — and still is — the first ointment applied to newborns.

This long history gives Shea butter a cultural status that most global consumers are unaware of. It’s not just a commodity — it’s a symbol of tradition, care, and continuity.

The Women Behind the Butter

Across Ghana and Burkina Faso, women are at the center of the Shea industry. From harvesting nuts to processing and churning the butter, the work is deeply gendered — and deeply manual.

A woman will often start by collecting fallen Shea fruits from under the trees during the harvest season (usually May to August).

She’ll then remove the pulp, wash the nuts, boil or dry them, and begin a multi-step process of crushing, roasting, milling, and kneading to eventually produce butter.

It's time-consuming, labour-intensive work — often done in open spaces or communal cooperatives.

Estimates suggest that over 80% of Shea production labor is done by women, and in total, around 16 million women across Africa are involved in the Shea value chain (Global Shea Alliance).

For many of them, this is their primary source of income — particularly in rural areas where formal employment is scarce.

Case Studies: Women’s Cooperatives Leading Change

Let’s zoom in on a few cooperatives that are transforming the narrative.

1. Star Shea Network, Ghana

Founded with the support of the Global Shea Alliance and USAID, this cooperative links over 5,000 women across northern Ghana.

They’ve been trained in sustainable harvesting, quality grading, and hygienic butter production.

What’s unique is their direct connection to international buyers — allowing them to bypass multiple intermediaries and earn higher margins.

The network also supports financial literacy and reinvests profits into community projects.

2. Nununa Federation, Burkina Faso

Based in Leo, a town in southern Burkina Faso, the Nununa Federation includes over 4,800 women across 45 villages.

They produce certified organic and fair-trade Shea butter, and supply companies in France, Canada, and Japan. They’ve set up their own processing facility, solar drying equipment, and even a microcredit scheme for members.

Nununa is a great example of local women taking ownership of the full value chain — from tree to export.

3. Savannah Fruits Company, Ghana

While technically a private company, Savannah Fruits works hand-in-hand with over 8,000 women processors in Northern Ghana.

They offer tools, training, and guaranteed purchase agreements for organic-certified butter.

Their processing facilities meet EU and US standards, and they work with cosmetics brands that prioritize ethical sourcing.

These models show what's possible when local producers are treated as partners, not just suppliers.

Ghana and Burkina Faso: A Shared Shea Economy

Though their national approaches differ, Ghana and Burkina Faso form a complementary economic ecosystem.

Burkina Faso is a top exporter of raw Shea nuts, often trading in bulk to buyers in Europe and Asia.

Ghana has invested more in processing, exporting refined butter and value-added products.

Their border regions are home to informal but powerful trade networks. Traders cross daily with nuts, butter, and goods.

Cultural and ethnic links blur national lines — creating a shared Shea identity that transcends political boundaries.

The Global Shea Boom

Demand for Shea butter has exploded in the past two decades — and shows no signs of slowing.

In the cosmetics and personal care industry, it’s a prized ingredient for its natural profile and multifunctionality. But Shea is also gaining traction in food industries as a cocoa butter alternative — especially since it’s non-GMO and has a long shelf life.

Some key facts:

Global Shea butter market size: Estimated at $2.6 billion in 2023, projected to reach $3.5 billion by 2028 (Research and Markets).

Europe accounts for over 40% of global imports, followed by the United States.

India, South Korea, and Japan are emerging markets for both bulk butter and cosmetic inputs.

Major international buyers include:

AAK (Sweden) – one of the world’s biggest Shea processors, sourcing from West Africa and refining in Europe.

L’Occitane (France) – one of the first major brands to source directly from women’s groups in Burkina Faso.

Unilever, L’Oréal, Beiersdorf – all use Shea in lotions, lip care, and hair products.

The Body Shop – markets its Shea line as "Community Trade" and sources from Ghanaian cooperatives.

Despite this growth, producers in Ghana and Burkina Faso capture only a small fraction of the final retail price.

The Value Gap

A 200-gram jar of Shea body butter might sell for $25 to $30 in a store in London or Tokyo.

The woman who processed the raw butter might have received $1.50 or less for her contribution.

This is the value gap that defines so many African exports — whether it’s cocoa, coffee, or Shea.

The further up the chain the product goes, the more money it generates — and the further removed it gets from the people who created it.

Add to this:

Climate vulnerability

Droughts, bushfires, and changing rainfall patterns are affecting Shea tree yields.Land pressure

As farmland expands, Shea trees are being cut down — especially without clear land tenure.Tech gaps

Many cooperatives lack processing machines, consistent power supply, or modern packaging tools.Certifications and compliance

Meeting global organic or fair trade standards requires audits, documentation, and training — which most producers cannot afford without external support.

Fixing this isn’t easy. But it’s possible.

What If West Africa Processed More?

Here’s where the opportunity lies: regional processing hubs.

If more Shea butter could be processed locally, rather than exported as raw nuts, West African countries could keep more value within the region. This doesn’t just mean making crude butter — it means setting up facilities that can produce cosmetic-grade, deodorised, or fractionated Shea to meet export specs.

Some emerging efforts include:

Ghana’s One District One Factory (1D1F) Initiative – supports agro-processing startups, including Shea.

Burkina Faso’s National Strategy for the Shea Sector – aims to boost certified processing capacity and export volumes.

Public-private partnerships – involving NGOs, donor agencies, and buyers like L’Occitane and AAK.

There’s also room for African brands to emerge — using Shea butter in local cosmetic products, selling both regionally and globally. Brands like:

Ajike Organics (Nigeria)

Tama Cosmetics (Ghana)

Karité (founded by three Ghanaian sisters based in the U.S.)

These players are proving that Africa doesn’t have to just supply raw materials — it can build brands, create jobs, and own the story.

Looking Ahead: A Natural Superpower

The Shea tree doesn’t need fertiliser, irrigation, or pesticides. It grows where little else does. It is resilient, low-carbon, and regenerative.

In many ways, it’s a perfect crop for the future — especially in a world increasingly looking for sustainable, ethical, and natural products.

Ghana and Burkina Faso are not just participants in this future — they are pioneers. Their knowledge, ecosystems, and community-led structures offer a model that could inspire other regions.

But the question remains: Who gets the value? Will Shea butter continue to be something processed and branded elsewhere? Or will the women who know the tree best finally lead the way?

If you found this story insightful, share it with a friend, colleague, or community that cares about ethical trade, African economies, or the future of natural beauty. Let’s bring more attention to the hands — and the trees — behind the world’s most loved ingredient.

Very informative! A lot of the issues with wages and prices globally remind me of the coffee trade in South America. It's a shame our lifestyle is still built off of cheap labor, even with stuff like Fair Trade meant to ensure labor rights!

Great piece! We noticed you've used some Tree Aid photographs in this piece, can you please credit Tree Aid under each one? Thanks!