The Invisible Nations: Former and Current Unrecognised States in Africa

A journey through Africa’s breakaway republics, rebel territories, and forgotten experiments in sovereignty.

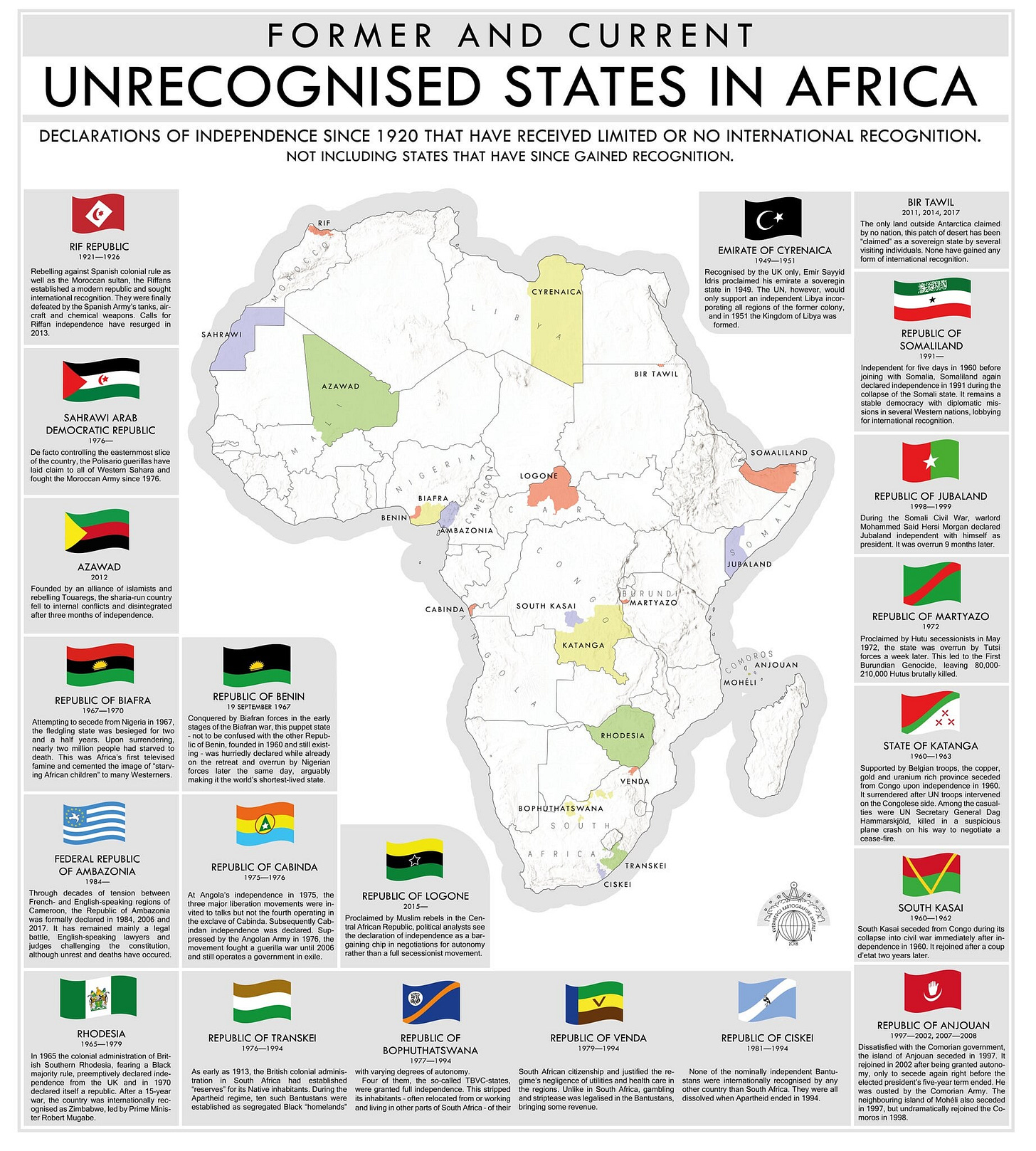

When you look at a map of Africa, you see sharp lines, tidy colors, and 54 officially recognized nations. But beneath this cartographic order lies a far messier story. Africa has been home to a surprising number of unrecognised states—places that declared independence, formed governments, minted currencies, and sometimes even fielded armies, but were never accepted as legitimate countries by the international community.

These breakaway republics, often born in the crucible of colonial legacy, ethnic identity, or political frustration, tell a deeper story about sovereignty, legitimacy, and the continuing impact of borders drawn by outsiders.

In this blog, we’ll explore these invisible nations—from the short-lived Republic of Biafra to the still-functioning Somaliland. Some flared up in civil wars, others emerged through peaceful declarations, and a few even resembled mini-states within states.

This is not just a history of failure. It’s a history of resilience, resistance, and questions that are still unanswered.

What Makes a State “Unrecognised”?

Let’s clear the air first. A state becomes "unrecognised" when it declares independence or claims sovereignty but is not widely acknowledged by other countries or international organizations like the United Nations. These states often fulfill many of the technical criteria for statehood—defined territory, permanent population, functioning government—but lack diplomatic recognition.

Recognition is political. It often depends less on legal legitimacy and more on international interests. That’s why Taiwan and Kosovo are partially recognized, while Somaliland—despite having peace, stability, and functioning institutions—is not.

Africa, with its colonial legacy and fragile post-independence institutions, has seen more than its share of these ghost states.

The Colonial Legacy: Drawing Borders Without Consent

Africa’s map was drawn not by Africans but by Europeans—mainly during the 1884 Berlin Conference. The borders ignored ethnic groups, languages, and cultural identities. Tribes were split across multiple countries. Rivals were forced into one political unit. What followed was inevitable: discontent, civil wars, and separatist movements.

Many of the unrecognised states in Africa emerged because people felt they were never truly part of the post-colonial nation they were told to belong to. Their grievances were often rooted in marginalization, underdevelopment, or outright oppression.

The Republic of Biafra (1967–1970): Nigeria’s Painful Fracture

Perhaps the most well-known unrecognised state in Africa, Biafra was declared in 1967 by the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria. Tensions had been simmering since independence in 1960, made worse by ethnic pogroms and economic disparities. When oil-rich Biafra declared independence, Nigeria responded with military force.

The Biafran War—or Nigerian Civil War—lasted three years and resulted in over a million deaths, many from starvation due to a blockade.

Though Biafra lost the war and was reabsorbed into Nigeria, its story left an indelible mark. It triggered humanitarian outrage worldwide and set the tone for how Africa—and the world—would deal with secession.

Recognition? Only a handful of countries, like Haiti and Gabon, acknowledged Biafra.

Somaliland (1991–Present): A Functioning State Without a Passport

In contrast to Biafra’s tragic collapse, Somaliland is a functioning democracy in the Horn of Africa that’s been waiting for recognition for over three decades.

After the fall of Somalia’s central government in 1991, Somaliland—a former British protectorate—declared independence. Since then, it has held elections, created a stable currency, maintained law and order, and even set up biometric voting systems.

But no UN member officially recognises it.

Why? Because the African Union and the international community fear setting a precedent that might encourage other secessionist movements. So, Somaliland remains in diplomatic limbo, trading stability for invisibility.

Azawad (2012): The Tuareg Dream That Briefly Took Flight

In 2012, Tuareg rebels in northern Mali declared the creation of Azawad, a secular independent state.

Their grievances weren’t new. For decades, the Tuareg—a nomadic Berber people—had complained of discrimination and neglect by Mali’s government. The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) quickly took control of the region during a military coup in Bamako.

But things unraveled fast.

Islamist groups hijacked the rebellion, imposing sharia law. France intervened militarily, and by 2013, Azawad was no more.

Though short-lived, Azawad showed how quickly power vacuums and internal chaos can undermine a separatist movement—even one rooted in deep historical identity.

Katanga (1960–63): Congo’s Copper-Rich Breakaway

Fresh from independence from Belgium, Congo was plunged into chaos when Katanga, its mineral-rich southeastern province, declared independence under Moïse Tshombe.

Katanga had everything: foreign investment, natural resources, a charismatic leader—and mercenaries. Belgium, concerned about its mining interests, backed the secession. The United Nations, however, took the side of Congo's central government.

A brutal military campaign followed. After three years, Katanga was reintegrated into Congo. But the scars remain. Today, Katanga is still a flashpoint for Congolese politics.

This case showed how foreign interests can shape secession outcomes, especially when valuable resources like copper and cobalt are involved.

South Kasai (1960–61): Congo’s Other Forgotten Republic

While Katanga hogged international headlines, South Kasai, another secessionist entity in Congo, quietly declared independence around the same time. Led by Albert Kalonji, it tried to create an ethnically-based state for the Baluba people.

But it lasted barely a year before being forcibly reintegrated. Thousands died, and the region was devastated.

South Kasai represents the ethnic fragmentation that can follow hasty decolonisation—when local identities feel threatened by national ones.

Cabinda (1975–Today): Angola’s Silent War

Cabinda is a small oil-rich enclave north of Angola, separated from the rest of the country by a strip of Congo. When Angola gained independence in 1975, Cabinda’s separatists declared their own state: the Republic of Cabinda.

Despite having its own history as a Portuguese protectorate, the separatist dream was crushed. Angola sent troops, and a guerrilla war ensued.

To this day, low-level insurgency continues. Most Angolans don’t even talk about it, and the government tightly controls the region. But the Republic of Cabinda still exists—in exile, with a flag, president, and diplomatic missions abroad.

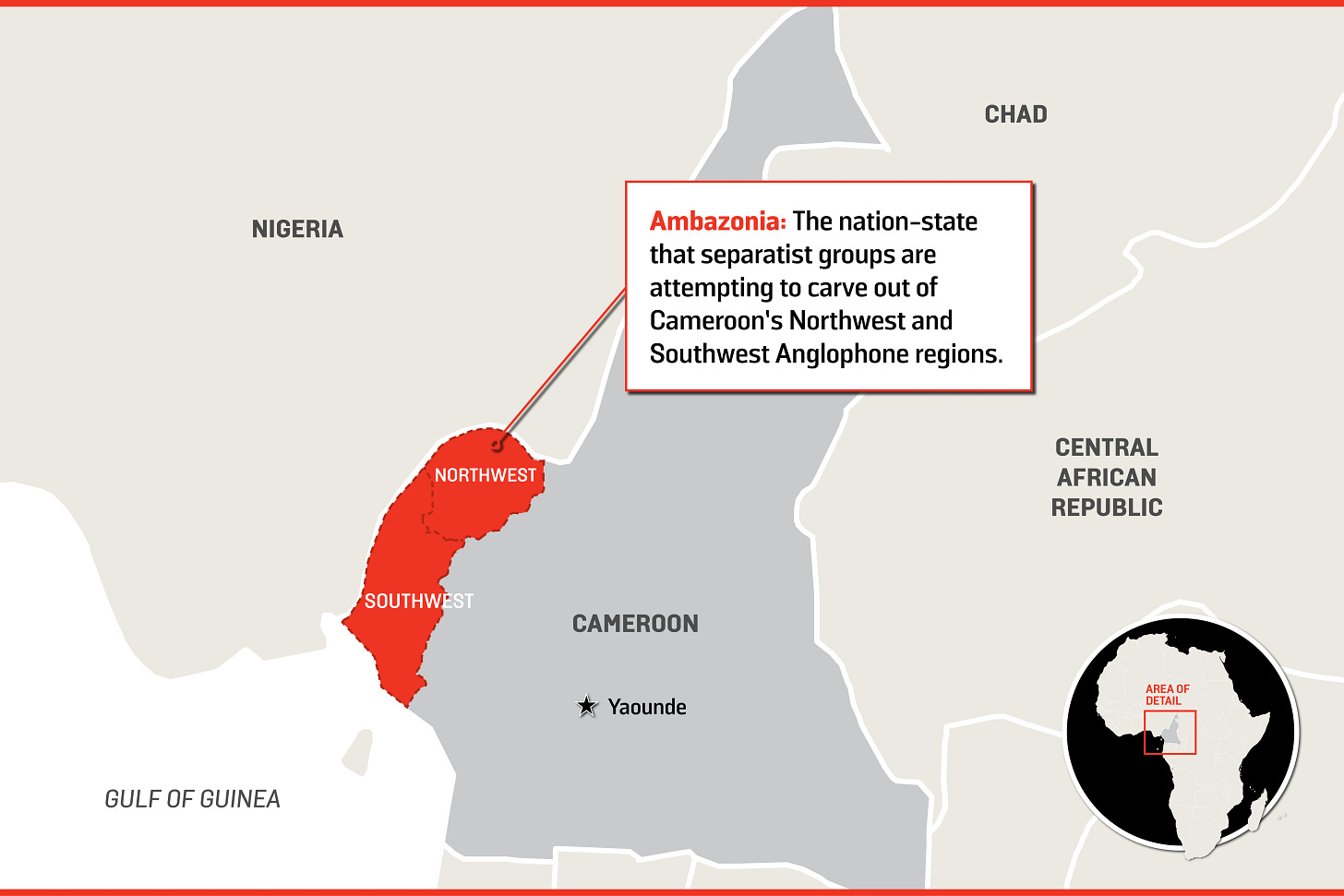

The Federal Republic of Ambazonia (2017–Present): Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis

In English-speaking parts of Cameroon, years of marginalization from the French-speaking majority led to the declaration of Ambazonia in 2017.

The government’s crackdown triggered a violent conflict. Over 6,000 people have died, and more than 700,000 have been displaced (source: Crisis Group, 2023).

Ambazonia has its own provisional government in exile. But recognition remains elusive. The world largely considers the conflict an internal matter—even as atrocities continue.

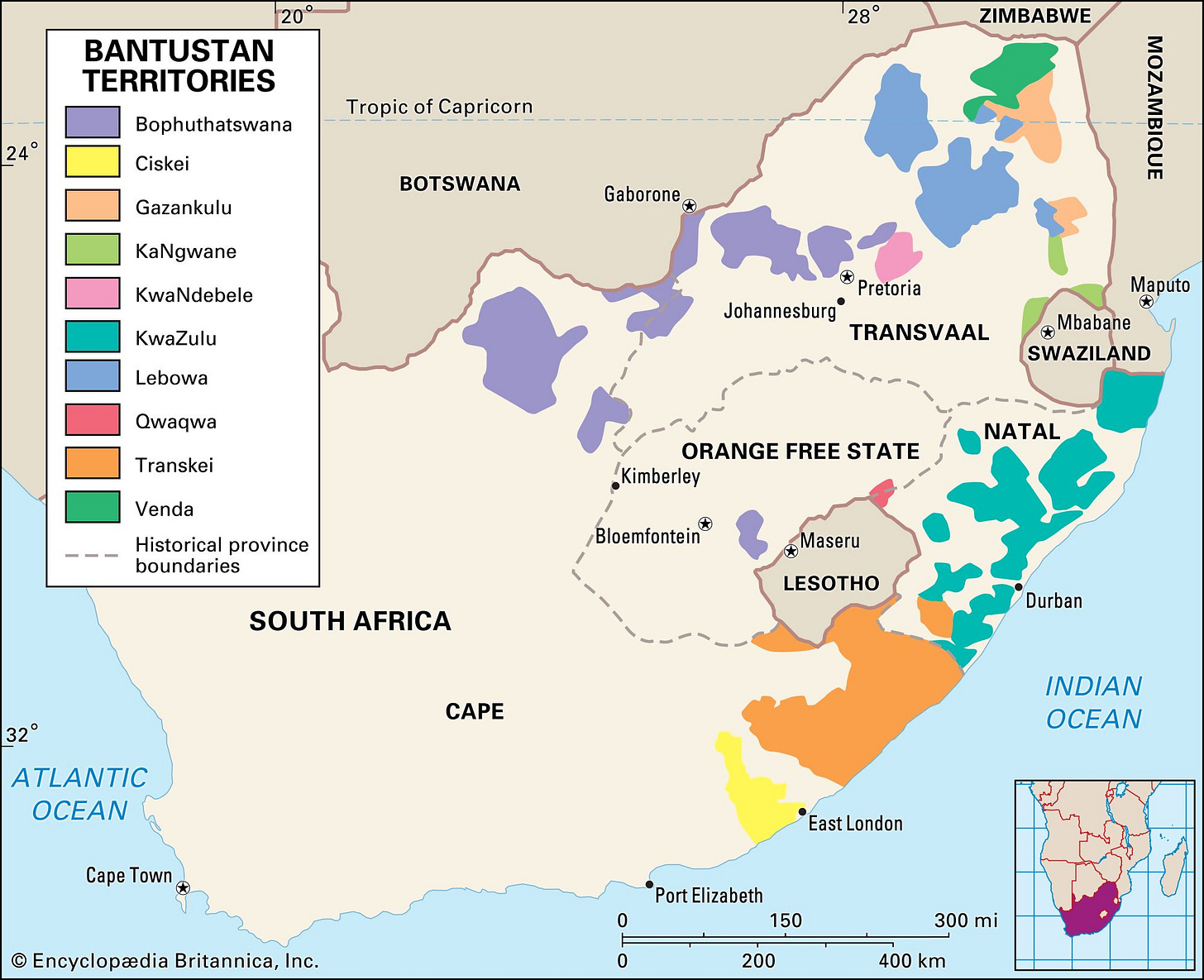

Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei: The Apartheid Puppets

South Africa, during apartheid, created “homelands” or Bantustans to segregate Black citizens and strip them of South African nationality. Four of these—Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei—were declared "independent."

But they were never recognised by anyone except South Africa.

These entities were often run by corrupt elites, dependent on Pretoria, and resented by their own people. After apartheid ended in 1994, these fake states were dissolved, and their territories reintegrated into democratic South Africa.

They stand today as symbols of how sovereignty can be manipulated for exclusion.

Somali Breakaway Zones: Jubaland and Puntland

While Somaliland functions as a quasi-state, Jubaland and Puntland in southern Somalia have also declared autonomy—though not full independence.

Both regions operate their own administrations and militaries. Puntland has even held elections. But they still officially remain part of Somalia.

These autonomous zones reveal the complex layers between autonomy, de facto control, and independence—especially in collapsed or fragile states.

Anjouan (1997–2008): The Island That Wanted France Back

In the Comoros Islands, Anjouan repeatedly tried to secede between 1997 and 2008. At one point, it even requested reintegration into France—ironically invoking its colonial past as a better option than political chaos.

The Comorian government rejected the moves, and Anjouan was brought back by military force with help from the African Union. But the story reflects how deep disillusionment can push people to seek drastic alternatives.

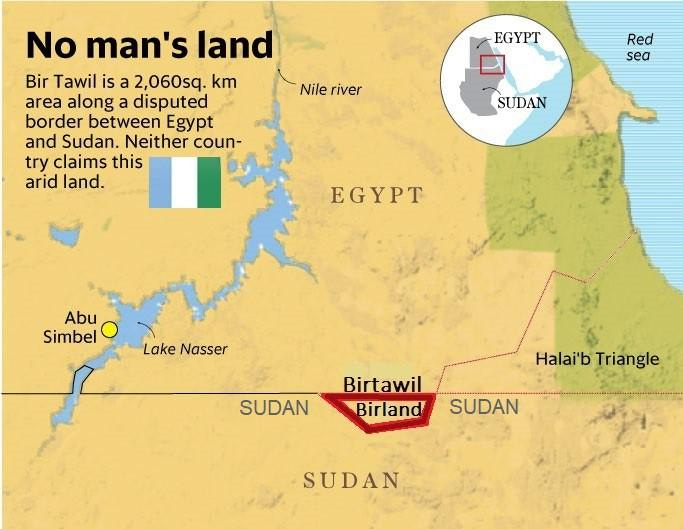

Bir Tawil: The Only Land Nobody Wants

Unlike every other case on this list, Bir Tawil is unclaimed—not by rebels, not by governments, not by anyone.

Located between Egypt and Sudan, this tiny desert strip is the result of overlapping border claims. In trying to assert control over the nearby Hala’ib Triangle, both countries refuse to claim Bir Tawil—since doing so would undermine their larger territorial claims.

A few individuals have tried to claim it as their own kingdom, including one American dad who declared himself king to make his daughter a princess.

It remains the only place on Earth where terra nullius—land belonging to no one—still exists.

What Do These Stories Tell Us?

From Biafra’s heartbreaking war to Somaliland’s quiet perseverance, Africa’s unrecognised states show that sovereignty is about more than maps. It's about identity, legitimacy, and governance. Some of these states were opportunistic grabs. Others were desperate bids for self-determination. A few succeeded, at least internally. Many collapsed into violence.

But all shared one thing: a desire to rewrite the political rules imposed by history.

In many ways, Africa’s unrecognised states reveal the continent’s ongoing struggle with borders that don’t reflect the people living within them.

Is the Map of Africa Truly Final?

The idea that African borders are sacrosanct is a political choice, not a geographic truth. The African Union, in its wisdom (and caution), has largely discouraged secession to maintain stability. But this comes at a cost—sometimes suppressing legitimate demands for self-rule or justice.

As the continent continues to urbanize, digitize, and integrate economically, these invisible states remind us that political legitimacy cannot be imposed—it must be earned.

In the 21st century, with the rise of decentralized governance, crypto economies, and global diasporas, will the next African state emerge not with a war—but with a Wi-Fi signal and a constitution in the cloud?